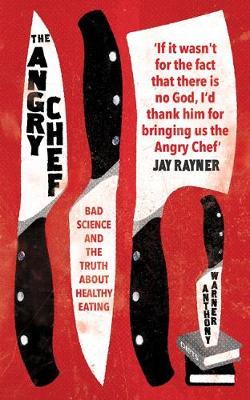

The angry chef: Bad science and the truth about healthy eating by Jay Rayner

One world, 2017. ISBN 9781786072160

(Age: 16+). Recommended. Diets. Nutrition. Scientific thinking. Jay

Rayner is the angry chef - he is angry about the false claims and

misconceptions peddled by the fad diet industry. He begins the book

with the story of the Easter lapwing. He describes the spring-time

discovery of hares often alongside scraped nests of colourful eggs -

giving birth to the medieval myth of the Easter bunny. However the

eggs had not been laid by the frolicking hares but by the elusive

wetland bird, the lapwing. People were fooled by the correlation of

hares and eggs and jumped to their own conclusions. It is human

nature to see correlation and assume causation - overlooking the

many possible confounding factors.

In his explose of fad diets, Ray presents many examples of mistaken

beliefs and pseudo-science, examples of mischievous hares sat next

to a pile of colourful eggs. He exposes the false science behind

each diet: from gluten-free, alkaline, detox, sugar-free,

carbohydrate-free, paleo, to the promotion of the wonder foods of

coconut oil and antioxidants, the dangers of the facile ideas of

clean eating, GAPS diet and cancer cures, the demonisation of

processed foods, the simplistic concept of good vs bad food. He

rants with anger at the false claims, the bullshit, and the fake

gurus that people seem to blindly follow, but his anger is tempered

with a good dose of humour that often made me laugh out loud.

And if there is anywhere to lay the blame for all this - it is our

education system. Instead of teaching scientific facts, he argues

that our science courses should be teaching the scientific method -

the need to look for and respect evidence and an understanding of

what constitutes proof. Science should teach children to doubt and

to question, and to learn about concepts such as 'regression to the

mean'. He says

'We should be trying to produce children who understand that

correlation is not always causation, that anecdotes are not

evidence, that a theory is not something dreamed up in a pub, and

that interesting results are often wrong.'

If you are curious about the food theories, he lays it all bare, in

an easy to read manner. I could imagine any of the chapters being

taken as a case study for a science class to examine the theories

and test the evidence. Rayner presents the statistics, the theories

and the laughs, and above all he promotes guilt-free enjoyment of

one of the great pleasures of life - food.

Helen Eddy